Few things ruin an otherwise really good day in the office more than a phone call from an upset postop patient. You know exactly what I’m talking about. The day is just flying along. You and all of the docs are spot on, running right on time without a single hiccup. No matter what your role is on the team, you are getting nothing but love from everyone; even the hyper-intense cataract surgeon—who’s not happy unless they’re an hour behind—was actually talking to a pharmaceutical rep.

Until the phone call comes.

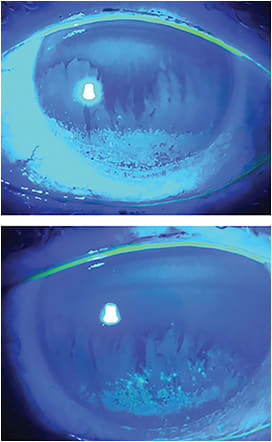

It’s a week post-op, and Mr. or Mrs. Blitzkrieg still has blurry vision and wants to know why they can’t read. Either the patient or the referring optometrist makes a call, and they are not happy. After setting the front desk phone on fire, they are transferred back to the surgical counselor who manages to talk them off the ledge and gets them to agree to come in for an emergency visit. This, of course, kicks the can down the road to the technician who has the privilege of working them up after they have dressed down the poor front desk staff and surgical counselor again on their way in. The tech has dealt with this before and knows what’s coming. Sure enough, the cornea lights up with fluorescein staining when the IOP is checked.

Another technically perfect surgery goes down in the flames of undetected and untreated dry eye disease (DED). Here’s how to prevent that scenario.

Make the diagnosis as early as possible

Depending on which study you read, anywhere from 20% to 80% of anterior segment surgical candidates have DED that can be diagnosed preoperatively. As many as 50% of them will be totally asymptomatic. This puts the onus on everybody in the office to make the diagnosis as early in the work-up process as possible. By doing so, it is possible to increase the likelihood of better outcomes and reduce postop surprises and unhappy patients. Whether your practice does standard cataract surgery, advanced refractive cataract surgery using what we call “premium” IOLs, or laser refractive surgery of any kind, the best time to make the diagnosis of DED is before doing the surgery. Eric Donnenfeld, MD, has the best explanation for why: “If you make the diagnosis of DED preop, it’s the patient’s problem; if you make it postop, it’s your problem.”

To understand why diagnosing and treating DED is critical, it is helpful to understand how important the pre-corneal tear film is to both ocular health and vision. Multiple studies have shown that DED can induce up to 3.00 D of corneal astigmatism. Imagine how hard it would be to get an accurate preop refraction for LASIK or K readings to pick an IOL power if you have DED preop! On top of that, every anterior segment surgical procedure temporarily causes an increase in dryness. While not every patient becomes symptomatic postop, the absence of a healthy tear film can dramatically slow down visual recovery. This is especially important when a multifocal IOL is chosen by patient and doctor. Even mild degrees of dryness can cause visual recovery to slow to a crawl.

How, then, do we diagnose DED before surgery? Thankfully you don’t need to be a referral practice that specializes in DED. Some very simple and straightforward strategies can be put in place to maximize the number of cases you catch before a patient gets into the operating room.

Get surgeons on board

Of course, it’s important that the surgeons in the practice are on board with this effort. Sometimes the dryness that is seen preop is so significant that you really need to postpone the surgery until it's under control. That’s a very hard decision to make without the support of the surgeons. It usually only takes a few unhappy post-op patients to get their attention and support.

Suss out symptoms

Making the DED diagnosis in symptomatic patients is easy: all you have to do is ask them! People who have classic DED symptoms (dryness, burning, tearing, grittiness, light sensitivity, etc.) are usually very unhappy about said symptoms. These patients are ready to tell you—if you are ready to listen.

In a preop patient, the logical place to have these discussions is in the technician work-up. The patient can fill out one of a number of established, verified patient surveys (OSDI, SANDE, SPEED) in the lobby or while dilating. It also can be as simple as asking a single question: “Do you take eyedrops?” If they say “yes,” it really doesn’t matter why they think they are taking the drops; the most likely reason is dry eye.

Distinguish asymptomatic patients

As I noted above, the tricky patients are those who are totally asymptomatic. No one is more surprised than they are at the clinical DED diagnosis that you make. Technicians do lots of things during a surgical work-up that can at least raise the suspicion of DED.

The place where most tech-driven diagnosis occurs is during applanation. When you look through the oculars, are the eyelids inflamed? Do they have telangiectatic blood vessels on the lid surface? Many times, the presence of plugged meibomian glands or cuffing around the base of lashes is very obvious when checking IOP. Make sure to take a quick look at the cornea after you instill fluorescein; staining on either the cornea or conjunctiva means DED.

Preop measurements for both cataract and refractive surgery are the next opportunity to find, and treat, DED. “Messy” mires on keratometry are as significant a finding as a topography that looks like Swiss cheese! Classically, you find the axes of your preop K values all over the map. How can you choose which one to use for your calculations? Of course, the answer is that you can’t — you have to treat the DED so that you can get accurate measurements that will give you predictable results.

Treat the issue

Now that everyone is on board the DED diagnosis train, how are we going to treat the patients you’ve identified? Much of this depends on the “style” of your practice — for example, how familiar your doctors and staff are with newer treatments. Regardless of your experience, it is important to consider speed and duration; you want to have DED treated before surgery as quickly as possible to minimize scheduling delays, and you want to treat long enough post-op to avoid those nasty phone calls.

Here are the go-to methods in our practice:

- Artificial tear. Every patient with a new DED diagnosis should be put on a high-quality artificial tear. Choose one of the all-purpose tears from any of the major companies, like Refresh Relieva (Allergan), Systane (Alcon), or Blink (Johnson & Johnson Vision). Treat through the entire post-op period.

- Topical steroids. If there are any measurement challenges, the fastest way to solve that problem and to move on to the OR is to prescribe topical steroids. Fluorometholone and loteprednol are highly effective when speed is important, and they tend to have fewer side effects (e.g. elevated IOP) if they need to be used for a longer period of time. Very often, your patient can get “over the hump” of the dryness effect of surgery by continuing to use steroid drops for 4 to 6 weeks after surgery. These are not ideal candidates for “no-drop” or “fewer drop” post-op regimens.

- Inflammatory inhibitors. As our practice has lots of experience with DED, we are quick to prescribe cyclosporine (0.005% Restasis, Allergan or 0.009% Cequa, Sun Pharma) or lifitegrast (5% Xiidra, Novartis) if there is enough dryness to make measurements difficult. Typically, these are long-term medications for 6 months.

Prevent the call that kills the vibe

Of course, much more can be done to diagnose and treat dry eye in the pre- and post-op period. Tear osmolarity is priceless in diagnosing that “silent” dry eye that becomes a post-op ambush. Likewise, imaging the meibomian glands and identifying either obstruction or destruction provides an opportunity to put both surgeon and patient on notice that DED may be an issue down the line. (For more information about diagnostic tests for DED, see p. 20.)

It’s certainly OK if you do not have these available, but they are a bonus if they are.

All that is necessary is a bit of awareness, a keen ear, a couple of targeted questions about symptoms, and a bit of extra care to look for the subtle signs of DED that can be picked up during the regular flow of an exam, like staining during applanation and sloppy mires when you are taking a K reading or doing topography.

These are the steps to take in order to prevent any staff members from having to take that call that kills the vibe in a day otherwise filled with nothing but unicorns and rainbows! OP