Cornea

Challenges of the cornea clinic

Part one of a seven-part corneal/anterior segment survival guide.

BY STEPHANIE MCMILLAN MHA, COA, AND MARTHA C. TELLO BGS, COMT, OSC

SERIES INTRODUCTIONBY KENDALL E. DONALDSON, MD, MS

A great ophthalmic technician is an extension of the physician — ideally, they work together seamlessly to provide the patient with the best overall experience and care. The position requires knowledge and skill. Ophthalmic practices place a lot of responsibility and trust in technicians, the first people to initiate clinical care on patients.

My team and I prepared this series of articles as a concise tool for the ophthalmic technician. Over the next several months, this series will guide the reader through the anterior segment examination, particularly in a general, cataract or cornea practice.

The team at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute. From left to right: Kendra Davis, COA; Martha C. Tello, BGS, COMT, OSC; Rosa Long, CRA; Stephanie McMillan, MHA, COA.

COURTESY BASCOM PALMER EYE INSTITUTE

Let me introduce the team. Stephanie D. McMillan, MHA, COA, the lead technician for Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Plantation, has been with Bascom Palmer for 11 years and has extensive expertise in refractions. Trained at the University of Florida in the Ophthalmic Technology and Orthoptic program, Martha C. Tello, BGS, COMT, works in clinical research and has served as the senior ophthalmic technologist for the Refractive Cataract clinic for the past 10 years. Stephanie and Martha developed a training program to help new technicians receive their certifications through JCAHPO. Rosa Long, CRA, has been with Bascom Palmer in Plantation for over seven years and contributes vast imaging and echography skills. She leads a team of photographers that image complex corneal and retinal disorders. Kendra Davis, COA, specializes in dry eye evaluations. She has been the technician for the Ocular Surface Center in Plantation for three years.

I feel privileged to work with such a knowledgeable, professional team. We hope this guide serves as a useful clinical tool as well as a guide to improve quality of patient care.

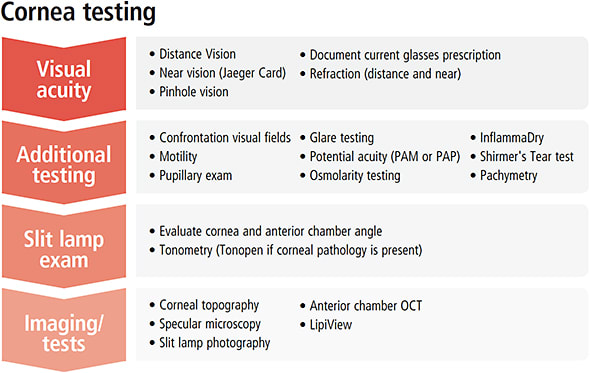

The cornea subspecialty encompasses a wide array of disorders and treatments. Corneal physicians may further sub-specialize in refractive surgery, refractive cataract surgery, ocular surface disease, or contact lenses. So, the cornea ophthalmic technician must be as multi-faceted as the cornea sub-specialty and skilled in complex refractions, performing intricate slit-lamp examinations, performing various corneal imaging technologies, and assisting the physician in various minor surgical procedures. The key to these duties is knowing how each procedure and test fits into the overall treatment and best clinical outcomes for the patient. Beyond vision testing, corneal ophthalmic technicians must perform on the highest level, anticipating the needs of both the patient and the physician.

Strategic work up

A complete cornea workup takes a combination of logic and knowledge and should put you on the right track toward probable diagnosis. Often, efficiency becomes an act of anticipation by giving the physician what he or she needs, and ultimately providing patients with the best medical care.

The initial work-up in a cornea clinic can reveal context into the patient’s general health, eye history, and behavioral/mental health. For example, women entering menopause can present with severe dry eye symptoms. Previous blepharoplasty or LASIK procedures could accelerate symptoms of eye discomfort. Some systemic medications, such as amiodarone, may result in classic chronic corneal changes, such as corneal verticillata. The cornea technician must document complex histories and perform difficult examinations, all while keeping the clinic flowing efficiently. Here, we will discuss some of the necessary duties that cover the cornea clinic work-up.

What to look for

History taking is the most useful and often the most overlooked portion of the technician’s exam. Clues in the patient’s past medical, surgical, and family history can provide possible links to the chief complaint.

| DIAGNOSIS | SYMPTOMS | SLIT LAMP FINDINGS | TEST TO PERFORM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fuch’s dystrophy | Early: No complaints Advanced Stages: Blurry Vision/ Fluctuating vision |

Guttatae, bullae | Specular microscopy |

| Keratoconus | Double vision, ghosting, glare and haloes. Poor vision | Cone shaped cornea, corneal hydrops, thinning of central cornea Check for Munson’s Sign |

Corneal topography |

| Dry eye | Foreign body sensation, tearing, pain | Superficial punctate keratitis/ Punctate epithelial staining | Schirmer’s, Tear Osmolarity, LipiView, TBUT |

| Corneal ulcer | Pain, poor vision, redness, possibly discharge | White corneal defect with staining | Slit lamp photo set up for possible corneal cultures |

| Contact lens-related problems/over-wear syndrome | Foreign-body sensation, non-tolerant to contact lens | Superficial punctate keratitis/punctate epithelial staining/pannus/giant papillary reaction | Slit lamp photo |

| HSV | Pain, foreign body sensation | Tree branch staining (dendrites) | Slit lamp photo |

| Graft rejection | Pain, redness, swelling, photophobia | Stromal edema, conjunctival injection | |

| Corneal perforation | Pain, irritation | + Seidel (wound leak) | Slit lamp photo |

| Pellucid marginal degeneration | Similar to keratoconus, double vision, ghosting, glare, and poor vision | Irregular shaped cornea, Hydrops | Corneal topography |

| Stromal edema | Blurry vision, chronic pain, discomfort | Descemet’s folds | Pachymetry |

| Filamentary keratitis | Foreign-body sensation, photophobia | Filaments | |

| Corneal scarring | Blurry or poor vision | White opacity | Slit lamp photo, anterior chamber OCT |

| Saltzman’s nodular dystrophy | Foreign-body sensation, poor vision | White opacities usually around the limbus | Slit lamp photo |

History taking requires these main points:

• Chief complaint. Why are you here today?

• Family history. Pertinent due to the genetic factors associated with certain cornea disorders.

• Past ocular surgeries. This includes cataract extraction, penetrating keratoplasty, radial keratotomy, LASIK, glaucoma surgery, retina surgery, conjunctival surgery, and eyelid surgery.

• Referring provider. It is ideal to inform physicians about prior diagnoses or procedures, as it may speed their ability to target potential treatment options.

• Primary care physician. Make a habit to keep this information up to date, as it comes in handy when scheduling surgery.

• Current and past ocular medications: The physician needs to know past treatments and whether they succeeded/failed to treat the problem to determine the best plan of treatment, and avoid wasting time with repeated, ineffective methods.

• Systemic diseases and medications. This may give context clues as to the patient’s overall health. Many of these diseases, such as diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, thyroid eye disease, or Sjögren’s Syndrome, have ocular manifestations, particularly when the underlying disease is under poor control. Additionally, some systemic medications used to treat the disease may have ocular side effects that present as blurry vision, dry eye, and other forms of vision loss or ocular irritation.

• Tobacco/alcohol use. Be specific on use and frequency. Heavy smokers may have severe dry eye symptoms due to exposure to the chronic irritant in cigarette smoke.

• Past general surgical history. Cosmetic surgery history, such as facelifts or blepharoplasty, are pertinent information for patients to share, as it may result in dry eye or exposure keratopathy associated with alterations in lid position or function many years after the initial surgery.

• Allergies: Environmental allergies can affect dry eye symptoms.

• Occupation/hobbies: A patient’s pastime may induce ocular symptoms either by the environment it creates or by the behavior it requires. For example, computer use with decreased blink rate, dusty environments with chemical conjunctivitis, and air conditioning causing surface drying, may all contribute to corneal pathology and resultant symptomatology.

Cornea workup Q&ABY KENDALL DONALDSON, MD, MS

Q: What is the normal amount of cells present for a specular microscopy versus someone with Fuch’s dystrophy?

A: Most of us are born with 2,800 to 3,200 endothelial cells, which then decrease with attrition at a slow rate throughout life. A normal, healthy 70-year-old adult should still have at least 1,500 cells, however we really only need about 700 endothelial cells to maintain a clear cornea. Once we start dipping below 700 cells, cornea edema starts to accumulate and the visual acuity begins to decrease. However, patients with guttate and no corneal edema may also be symptomatic as they experience glare and decreased quality of vision due to the pattern of light refraction off of the irregular lining of the cornea.

Q: What do you consider the most critical part of the cornea work up?

A: My gut reaction to this question is “the refraction.” An excellent detail-oriented refractionist is indispensable to the corneal surgeon. Many of our complex patients have irregular corneal surfaces and may be very difficult to refract. Many times, the determination of the patient’s best corrected visual acuity can key us in to early detection of new pathology or may trigger us to recognize a change in their underlying disease state. I consider the corneal topography or tomography mapping would be the second most important part. However, many times the refraction and the topography go hand-in-hand.

Q: What is the difference between keratoconus and pellucid marginal degeneration (PMD)?

A: Keratoconus (top below) and PMD (bottom below) are both bilateral (but possibly asymmetric) ectatic (degenerative) disorders of the cornea. Pellucid is characterized by a clear central cornea, generally of normal thickness with inferior peripheral thinning resulting in significant irregular astigmatism. Keratoconus is also characterized by inferior steepening; however, this condition has more central thinning slightly inferior to the corneal apex. On topography, pellucid is characterized by a characteristic pattern shaped like a “handlebar mustache,” whereas keratoconus is characterized by a “potbelly.”

Topography images of patients with keratoconus (top) and PMD (bottom).COURTESY PHOTO CREDITS

What do you see?

Vision testing encompasses involves using your judgment and clinical protocols to gauge the patient’s responses and document them effectively. The technician should start with the Snellen chart, and go to the smallest line. In the event patient cannot read letters, turn to the E chart card, and measure distance in feet. Besides, if the patient is not able to see the E card, the ophthalmic technician should turn to counting fingers, hand movement, and light perception assessment. OP

Part two will detail the refractive/cataract workup.

|

Kendall E. Donaldson, MD, MS, is associate professor of ophthalmology and medical director of Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Plantation, Fla. |

|

Stephanie D. McMillan, MHA, COA, is the lead ophthalmic technician and a clinical and informatics trainer at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Plantation, Fla. She is currently obtaining her COT certification. |

|

Martha C. Tello, BGS, COMT, OSC, is an ophthalmic technologist and clinical research coordinator with Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Plantation, Fla. She has a Bachelor’s Degree in Leadership and Communication from University of Miami. |