Practice Management

Understand the meaning behind the codes by reviewing ICD-10 basics

Take advantage of the time you have to ease the transition to the new coding system.

BY KIMBERLY BALDWIN, MA, LPC, DENVER, COLO.

You’ve heard of ICD-10 and you know it means big changes. You’ve read about making that transition in the September/October issue of Ophthalmic Professional. But now you’re feeling pressured to get your act together and organize a plan. Do you really understand what the changes are or how they will impact your practice?

Are you fully prepared for all the possible disruptions the change will bring? How long will it take the entire health-care system to adjust to the structure of ICD-10? More importantly, how long will it take you? You’re not sure you have it in you to memorize a whole new set of codes. It’s the next big obstacle to overcome, and you’ve got to start training now to conquer it. Don’t fret, you’ve already mastered ICD-9, you can do this!

Basic Structure

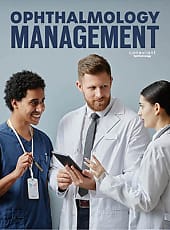

ICD-10 codes can be as few as three or as many as seven characters. The codes will always have three characters before the decimal and as many as four after. The first character is always alphabetic (but never a “U”) and the second character is always numeric; the rest of them can be either alphabetic (capitalization doesn’t matter) or numeric. In ophthalmology, most of the codes will begin with “H.” However, if it is endocrine related, such as diabetic-related cataracts or retinopathy, it will begin with an “E” for Endocrine. For an example, see Figure 1.

ICD-10 curveball: increased specificity

ICD-10 also brings increased specificity to coding. Diagnosis codes will need to specify either right eye (1), left eye (2), both eyes (3), or unspecified (9).

The seventh spot indicates the specified eye.

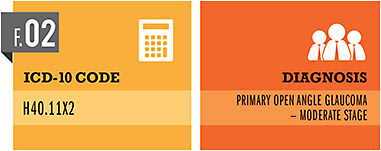

Placeholder codes (marked as an “x,” usually at the sixth seat) are new to ICD-10. They exist if the seventh number has significance, but the sixth does not. The seventh character of an ICD-10 code describes different things depending on the condition. In the case of primary open-angle glaucoma (Figure 2), the use of the seventh character will indicate the level of severity or the stage of the disease.

General Equivalence Mappings

General Equivalence Mappings (GEMs) were developed by the National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and others. Their aim was to create an ICD-9-to-ICD-10 dictionary. An admirable effort, but like traveling abroad with only a phrase-book, the nuances are lost. ICD-10 has more than four times the amount of codes of ICD-9. Imagine the English alphabet with 100 characters instead of 26.

According to the American Health Information Management Association, “It is important to note that the GEMs are not direct crosswalks, because there is not a one-to-one correlation between ICD-9-CM and the more complex ICD-10-CM/PCS”. The American Academy of Professional Coders has a great GEM’s tool on their website which allows you to search codes bi-directionally. (https://www.aapc.com/ICD-10/icd-10-codes.aspx).

The Finish Line

It isn’t all going to be an uphill battle. In some cases, combination codes make things easier. In ICD-9 if you had a patient with diabetes who had ophthalmic complications (such as cataracts) you would submit two codes to the payers to indicate the underlying condition causing the cataract. In ICD-10, you only have to submit one code — E10.36, indicating diabetes mellitus with diabetic cataract.

Many tools are available for free on the Internet and, as always, the collective knowledge of your peers is greater than one person training for a marathon alone. Create an interoffice “cheat sheet” and make an effort to share new information freely in your offices. Know when to get help and seek out experts who can give you focus. OP

|

Kimberly Baldwin, MA, LPC, is a consultant, designer and solutions expert for Destinations Consulting with more than 20 years experience in ophthalmology. She is based out of Denver, Colo. |