Case Study

What? I have an Rx check?

When patients complain about their new eyewear, it can pay to become an investigator.

Sergina M. Flaherty, COMT

In an ophthalmology practice, ophthalmic technicians perform refractometry many times over the course of their workday. Ophthalmologists review the resulting manifest refraction data and, using their clinical judgment, prescribe glasses from this information. The patient then takes this written prescription (Rx) to an optical shop to purchase new glasses. In the majority of instances, patients are completely satisfied with the vision correction provided by their new eyewear.

Occasionally, however, the patient will call to complain they are unable to see well with their new glasses. When patients who I have refracted return with such complaints, it has always been a priority of mine to personally re-refract them to determine the cause of the problem. Was it something I did in performing refractometry that caused this complaint, or is something else to blame?

In my long career in ophthalmology, I have seen many different reasons for this dissatisfaction with a new spectacle prescription. Interestingly, I have found a number of cases where the prescription is not the cause at all.

The Prescription Check: A Learning Experience

Today, I consider an Rx check an opportunity to learn — I become an investigator. I ask every patient to bring the new glasses with them to the appointment. I then read the lens powers on a lensometer to confirm the prescription was ground correctly. If the lenses are correct, I have the patient put the glasses on and I measure their visual acuity. If their acuity matches what they were able to see during the initial manifest refraction, I then have to find another reason for the complaint.

This is where it gets interesting. I would like to share several refractometry cases that have required re-refractions along with the steps I have taken to understand the cause of the complaint.

PATIENT #1: “I just picked up my new pair of glasses and when I put them on, I can’t see anything out of my left eye – everything is a big blur. However, I can see okay with my old glasses. What should I do?”

First, I confirm his complaint when he’s in the exam chair. There, he told me, “you’re going to think I’m crazy, but I can’t see anything with my left eye out of these glasses.”

I measured his spectacle lenses on the lensometer and found the right lens was correct, but the left lens was 90 degrees off axis. The original Rx was written −2.00 +2.75 × 180; instead I measured it as −2.00 +2.75 × 90. I checked his visual acuity and sure enough he measured 20/cf with his left eye. I placed the incorrect prescription in the phoropter and slowly turned the axis dial toward the correct axis and stopped at 180°. At that moment, the patient was surprised and happy that he could see. He was relieved that he “was not crazy,” and that I found the problem.

It appears that an employee at the optical shop tried to transpose our prescription into minus cylinder. They performed the first part of the transposition correctly, but didn’t rotate the axis 90 degrees. The patent returned to the optical shop and they remade the left lens correctly.

Figure 1: Due to a head tilt, the patient looked through the intermediate segment of her lenses to see distances, resulting in blurred vision. This was due to a head tilt Figure 2: She was able to see clearly through the distance segment once she positioned her head erect and brought her chin down. |

PATIENT #2: “I’m having trouble seeing at distance with these progressive bifocals.”

First, I checked the lenses and confirmed the prescription was made correctly and that the segment measurements were correctly ground into these lenses. Then, I measured the patient’s vision wearing the progressives. What I noticed was the patient tilted her head back with her chin up, which caused her to look through the intermediate segment of the progressive lens.

This action by the patient caused induced plus power and resulted in blurred distance vision. I gently made the patient aware of the head tilt and asked her to bring her chin down, which positioned her head erect and she then was able to see clearly through the distance segment of the progressive lenses. (See figures 1 and 2.)

PATIENT #3: “I have had my new glasses for one month. Initially, I could see pretty well with them. However, now I can’t see to read with my right eye.”

I checked the lenses on the lensometer and found them to be accurately made. I checked the patient’s vision — his right eye was 20/50 and his left eye was 20/25. In reviewing this patient’s chart, it was noted that the right eye had drusen and best-corrected vision with the manifest refraction was 20/30.

I performed refractometry and was unable to improve the visual acuity in the right eye. I performed an amsler grid test; the patient described a blurry gray spot very near the central fixation point. I dilated the patient and asked the ophthalmologist to see him. The ophthalmologist said his right eye had developed a wet form of macular degeneration (neovascular or exudative AMD) and referred the patient to a retinal specialist. Unfortunately in this case, this patient’s vision could not be improved with a change in his prescription for vision correction.

PATIENT #4: “My vision is poor with these glasses when I try to see up close, especially using my left eye.”

I first checked the lenses and confirmed the prescription was made correctly. Visual acuity was 20/20 right eye and 20/30 left eye at distance. Near vision was found to be 20/20 right eye and 20/40 left eye. I looked back at the visual acuity measurements of the original manifest refraction. The chart indicated that the examination was normal and the patients vision was corrected to 20/20 both eyes at distance and near.

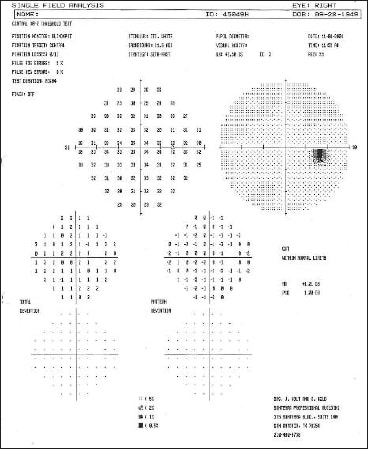

I performed refractometry and was unable to improve the visual acuity in the left eye. When I discussed these findings with the ophthalmologist, she suggested we preform another dilated examination. Upon pupil evaluation, I found a trace of a Marcus Gunn pupil OS. Hearing of the afferent pupillary defect, or APD, the ophthalmologist ordered a visual field on both eyes. (See figure 3.)

Figure 3. The visual field shows a defect in the left eye.

The ophthalmologist performed a complete retinal evaluation and found the optic nerves in both eyes to be normal. However, with theMarcus Gunn pupil and the visual field defect in the left eye, she ordered an MRI to rule out retrobulbar neuritis and Multiple Sclerosis.

The MRI results confirmed an MS diagnosis and the patient was referred promptly to a specialist for evaluation and treatment.

Fortunately, it was a presumed glasses problem that brought these last two cases back to our office. There, we could help determine that a disease process was occurring and refer them for appropriate treatment. OP

|

Ms. Flaherty is a Certified Ophthalmic Medical Technologist at Stone Oak Ophthalmology in San Antonio, Texas. She is owner of Ophthalmic Seminars of San Antonio and conducts instructional seminars to ophthalmic assistants and technicians in Texas and nationally. She is currently the JCAHPO representative on the board of Directors of the Association of Technical Personnel in Ophthalmology (ATPO). You contact Sergina by visiting her website www.ophthalmicseminars.com |